The SILVER AGE

c. 1956 - C. 1970

The Silver Age of Comic Books was a period of artistic advancement and commercial success in mainstream American comic books, predominantly those in the superhero genre. Following the Golden Age Of Comic Books - and an interregnum in the early to mid-1950s - the Silver Age is considered to cover the period from 1956 to circa 1970.

So, as the the popularity of superhero comics waned during the late 1940s, and comic book publishers diversified into genres such as war, Westerns, science fiction, romance, crime, and horror to retain reader interest, many superhero titles were cancelled or converted to other genres:

In 1953, the comic book industry hit a major set back when the US Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency was created to investigate the problem of juvenile delinquency. After Fredric Wertham's book Seduction Of The Innocent (1954) claimed that comics sparked illegal behavior among minors, comic book publishers were subpoenaed to testify in public hearings.

As a result, the Comics Code Authority was created by the Association Of Comics Magazine Publishers to enact self-censorship by comic book publishers, marking the start of a new era.

- In 1946, DC Comics' Superboy, Aquaman and Green Arrow were switched from More Fun Comics into Adventure Comics so More Fun could focus on humor.

- In 1948, All American Comics - featuring Green Lantern, Johnny Thunder and Dr. Midnite - was replaced with All-American Western.

- The following year, Flash Comics and Green Lantern were cancelled.

- In 1951, All Star Comics, featuring the Justice Society of America, became All-Star Western.

- The next year, Star-Spangled Comics, featuring Robin, was retitled Star Spangled War Stories.

- Sensation Comics, featuring Wonder Woman, was cancelled in 1953.

- Plastic Man appeared in Quality Comics' Police Comics until 1950, when its focus switched to detective stories.

- Timely Comics' The Human Torch was cancelled with issue #35 (March 1949).

- Marvel Mystery Comics, featuring the Human Torch, was canceled with issue #92 (June 1949, when it became the horror comic Marvel Tales).

- Sub-Mariner Comics was cancelled with issue #32 (June 1949).

- Captain America Comics, by then Captain America's Weird Tales, was cancelled with #75 (February 1950).

- Harvey Comics' Black Cat was cancelled in 1951 and rebooted as a horror comic later that year.

- Lev Gleason Publications' Daredevil was edged out of his title by the Little Wise Guys in 1950.

- Fawcett Comics' Whiz Comics, Master Comics and Captain Marvel Adventures were cancelled in 1953, and The Marvel Family was cancelled the following year.

In 1953, the comic book industry hit a major set back when the US Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency was created to investigate the problem of juvenile delinquency. After Fredric Wertham's book Seduction Of The Innocent (1954) claimed that comics sparked illegal behavior among minors, comic book publishers were subpoenaed to testify in public hearings.

As a result, the Comics Code Authority was created by the Association Of Comics Magazine Publishers to enact self-censorship by comic book publishers, marking the start of a new era.

In the wake of these changes, publishers began introducing superhero stories again.

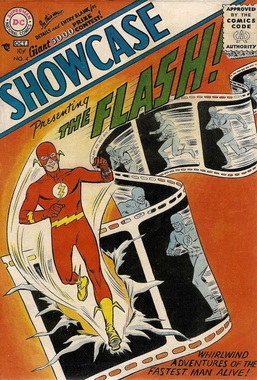

In 1956, DC editor Julius Schwartz assigned writer Robert Kanigher and artists Carmine Infantino and Joe Kubert to the company's first attempt at reviving superheroes: an updated version of the Flash that would appear in Showcase #4 (October 1956).

Julius Schwartz also edited "Flash of Two Worlds" in The Flash #123 (September 1961). It introduces Earth-Two, and, more generally, the concept of the multiverse to DC Comics.

The eventual success of the new, science-fiction oriented Flash heralded the wholesale return of superheroes, and the beginning of what fans and historians call the Silver Age Of Comic Books.

At the time, only three superheroes - Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman - were still published under their own titles.

In 1956, DC editor Julius Schwartz assigned writer Robert Kanigher and artists Carmine Infantino and Joe Kubert to the company's first attempt at reviving superheroes: an updated version of the Flash that would appear in Showcase #4 (October 1956).

Julius Schwartz also edited "Flash of Two Worlds" in The Flash #123 (September 1961). It introduces Earth-Two, and, more generally, the concept of the multiverse to DC Comics.

The eventual success of the new, science-fiction oriented Flash heralded the wholesale return of superheroes, and the beginning of what fans and historians call the Silver Age Of Comic Books.

At the time, only three superheroes - Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman - were still published under their own titles.

With the success of Showcase #4, several other 1940s superheroes were reworked; only the characters' names remained the same; their costumes, locales, and identities were altered, and imaginative scientific explanations for their superpowers generally took the place of magic as a modus operandi in their stories. Comic book readers of the Silver Age were more scientifically-inclined than previous generations. Thus, comic books of the Silver Age explained superhero phenomenons and origins through science, as opposed to the Golden Age, which commonly relied on magic or mysticism. For example, the Golden Age character the Green Lantern (railroad engineer Alan Scott) possessed a ring powered by a magical lantern, but his Silver Age replacement, test pilot Hal Jordan, had a ring powered by an alien battery and created by an intergalactic police force.

Newly introduced heroes included Green Lantern (Showcase #22, October 1959), The Atom (Showcase #34, October 1961), and Hawkman (The Brave And The Bold #34, March 1961), as well as the Justice League Of America (an updating of The Justice Society Of America), debuting in The Brave and the Bold #28 (March 1960), and receiving its own title in October 1960. It became one of the most successful series of the Silver Age.

Following the success of DC's Justice League Of America - a team consisting of the company's most popular superhero characters - Martin Goodman, a publishing trend-follower with his 1950s Atlas Comics line (by this time called Marvel Comics), "mentioned that he had noticed one of the titles published by National Comics seemed to be selling better than most. It was a book called The [sic] Justice League of America and it was composed of a team of superheroes," Marvel editor Stan Lee recalled in 1974. Goodman directed Lee to likewise produce a superhero team book, resulting in The Fantastic Four #1 (November 1961).

Under the guidance of writer-editor Stan Lee and artists/co-plotters such as Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, Marvel began its own rise to prominence. With an innovation that changed the comic-book industry, The Fantastic Four #1 initiated a naturalistic style of superheroes with human failings, fears, and inner demons, who squabbled and worried about the likes of rent-money. In contrast to the straitlaced archetypes of superheroes at the time, this ushered in a revolution. With dynamic artwork by Kirby, Steve Ditko, Don Heck, and others complementing Lee's colorful, catchy prose, the new style became popular among college students who could identify with the angst and the irreverent nature of the characters such as Spider-Man, the X-Men and the Hulk during a time period of social upheaval and the rise of a youth counterculture.

Newly introduced heroes included Green Lantern (Showcase #22, October 1959), The Atom (Showcase #34, October 1961), and Hawkman (The Brave And The Bold #34, March 1961), as well as the Justice League Of America (an updating of The Justice Society Of America), debuting in The Brave and the Bold #28 (March 1960), and receiving its own title in October 1960. It became one of the most successful series of the Silver Age.

Following the success of DC's Justice League Of America - a team consisting of the company's most popular superhero characters - Martin Goodman, a publishing trend-follower with his 1950s Atlas Comics line (by this time called Marvel Comics), "mentioned that he had noticed one of the titles published by National Comics seemed to be selling better than most. It was a book called The [sic] Justice League of America and it was composed of a team of superheroes," Marvel editor Stan Lee recalled in 1974. Goodman directed Lee to likewise produce a superhero team book, resulting in The Fantastic Four #1 (November 1961).

Under the guidance of writer-editor Stan Lee and artists/co-plotters such as Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, Marvel began its own rise to prominence. With an innovation that changed the comic-book industry, The Fantastic Four #1 initiated a naturalistic style of superheroes with human failings, fears, and inner demons, who squabbled and worried about the likes of rent-money. In contrast to the straitlaced archetypes of superheroes at the time, this ushered in a revolution. With dynamic artwork by Kirby, Steve Ditko, Don Heck, and others complementing Lee's colorful, catchy prose, the new style became popular among college students who could identify with the angst and the irreverent nature of the characters such as Spider-Man, the X-Men and the Hulk during a time period of social upheaval and the rise of a youth counterculture.

The Silver Age of Comic Cooks was followed by The Bronze Age. The demarcation is not clearly defined, but there are a number of possibilities. Historian Will Jacobs suggests the Silver Age ended in April 1970, when the man who had started it, Julius Schwartz, handed over Green Lantern - starring one of the first revived heroes of the era - to the new team of Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams, in response to reduced sales.

John Strausbaugh (journalist, cultural commentator) also connects the end of the Silver Age to Green Lantern. He observes that in 1960, the character embodied the can-do optimism of the era, declaring:

"No one in the world suspects that at a moment's notice I can become mighty Green Lantern – with my amazing power ring and invincible green beam! Golly, what a feeling it is!"

However, by 1972 Green Lantern had become world weary:

"Those days are gone – gone forever – the days I was confident, certain ... I was so young ... so sure I couldn't make a mistake! Young and cocky, that was Green Lantern. Well, I've changed. I'm older now ... maybe wiser, too ... and a lot less happy."

Strausbaugh writes that the Silver Age "went out with that whimper."

Comics scholar Arnold T. Blumberg places the end of the Silver Age in June 1973, when Gwen Stacy, girlfriend of Peter Parker (Spider-Man) was killed in a story arc later dubbed "The Night Gwen Stacy Died", saying the era of "innocence" was ended by "the 'snap' heard round the comic book world - the startling, sickening snap of bone that heralded the death of Gwen Stacy."

Silver Age historian Craig Shutt disputes this, saying:

"Gwen Stacy's death shocked Spider-Man readers. Such a tragedy makes a strong symbolic ending. This theory gained adherents when Kurt Busiek and Alex Ross' Marvels miniseries in 1994 ended with Gwen's death, but I'm not buying it. It's too late. Too many new directions - especially [the sword-and-sorcery trend begun by the character] Conan and monsters [in the wake of the Comics Code allowing vampires, werewolves and the like] - were on firm ground by this time."

He also dismisses the end of the 12-cent comic book, which went to 15 cents as the industry standard in early 1969, noting that the 1962 hike from 10 cents to 12 cents had no bearing in this regard. Shutt's line comes with Fantastic Four #102 (September 1970); Jack Kirby's last regular-run issue before he left to join DC Comics; this combines with DC's Superman #229 (August 1970), editor Mort Weisinger's last before retiring after being a longtime editor for the various Superman titles, and to be replaced by Julius Schwartz. Schwartz set about toning down some of the more fanciful aspects of the Weisinger era, removing most Kryptonite from continuity and scaling back Superman's nigh-infinite powers.

John Strausbaugh (journalist, cultural commentator) also connects the end of the Silver Age to Green Lantern. He observes that in 1960, the character embodied the can-do optimism of the era, declaring:

"No one in the world suspects that at a moment's notice I can become mighty Green Lantern – with my amazing power ring and invincible green beam! Golly, what a feeling it is!"

However, by 1972 Green Lantern had become world weary:

"Those days are gone – gone forever – the days I was confident, certain ... I was so young ... so sure I couldn't make a mistake! Young and cocky, that was Green Lantern. Well, I've changed. I'm older now ... maybe wiser, too ... and a lot less happy."

Strausbaugh writes that the Silver Age "went out with that whimper."

Comics scholar Arnold T. Blumberg places the end of the Silver Age in June 1973, when Gwen Stacy, girlfriend of Peter Parker (Spider-Man) was killed in a story arc later dubbed "The Night Gwen Stacy Died", saying the era of "innocence" was ended by "the 'snap' heard round the comic book world - the startling, sickening snap of bone that heralded the death of Gwen Stacy."

Silver Age historian Craig Shutt disputes this, saying:

"Gwen Stacy's death shocked Spider-Man readers. Such a tragedy makes a strong symbolic ending. This theory gained adherents when Kurt Busiek and Alex Ross' Marvels miniseries in 1994 ended with Gwen's death, but I'm not buying it. It's too late. Too many new directions - especially [the sword-and-sorcery trend begun by the character] Conan and monsters [in the wake of the Comics Code allowing vampires, werewolves and the like] - were on firm ground by this time."

He also dismisses the end of the 12-cent comic book, which went to 15 cents as the industry standard in early 1969, noting that the 1962 hike from 10 cents to 12 cents had no bearing in this regard. Shutt's line comes with Fantastic Four #102 (September 1970); Jack Kirby's last regular-run issue before he left to join DC Comics; this combines with DC's Superman #229 (August 1970), editor Mort Weisinger's last before retiring after being a longtime editor for the various Superman titles, and to be replaced by Julius Schwartz. Schwartz set about toning down some of the more fanciful aspects of the Weisinger era, removing most Kryptonite from continuity and scaling back Superman's nigh-infinite powers.