The BRONZE AGE

ca. 1970 - ca. 1985

The Bronze Age Of Comic Books is usually said to run from 1970 to 1985.

The Bronze Age retained many of the conventions of the Silver Age, with traditional superhero titles remaining the mainstay of the industry. However, a return of darker plot elements and more socially relevant story-lines (akin to those found in the Golden Age Of Comic Books) featuring real-world issues, such as drug use, alcoholism, and environmental pollution, began to flourish during the period, prefiguring the later Modern Age Of Comic Books.

There is no one single event that can be said to herald the beginning of the Bronze Age. Instead a number of events at the beginning of the 1970s, taken together, can be seen as a shift away from the tone of comics in the previous decade.

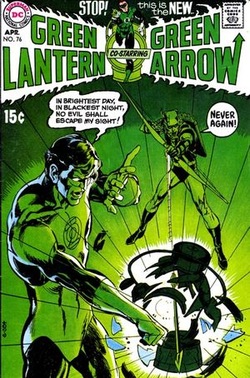

One such event was the April 1970 issue of Green Lantern, which added Green Arrow as a title character. The series, written by Denny O'Neil and penciled by Neal Adams (with inking by Adams himself or Dick Giordano), focused on "relevance" as Green Lantern was exposed to poverty and experienced self-doubt.

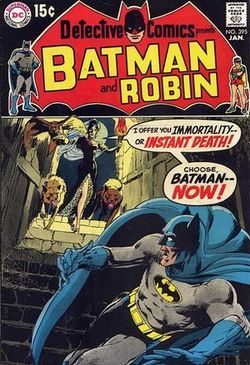

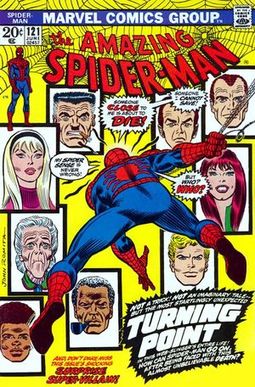

The death of Spider-Man's girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, at the hands of the Green Goblin in Amazing Spider-Man #121-122 (June-July 1973) is considered by comics scholar Arnold T. Blumberg to be the definitive Bronze Age event, as it exemplifies the period's trend towards darker territory and willingness to subvert conventions such as the assumed survival of long-established, "untouchable" characters. However, there had been a gradual darkening of the tone of superhero comics for several years prior to "The Night Gwen Stacy Died", including the death of her father in Amazing Spider-Man #90 (November 1970) and the beginning of the Dennis O'Neil/Neal Adams tenure on Batman (Detective Comics #395, January 1970).

The Bronze Age retained many of the conventions of the Silver Age, with traditional superhero titles remaining the mainstay of the industry. However, a return of darker plot elements and more socially relevant story-lines (akin to those found in the Golden Age Of Comic Books) featuring real-world issues, such as drug use, alcoholism, and environmental pollution, began to flourish during the period, prefiguring the later Modern Age Of Comic Books.

There is no one single event that can be said to herald the beginning of the Bronze Age. Instead a number of events at the beginning of the 1970s, taken together, can be seen as a shift away from the tone of comics in the previous decade.

One such event was the April 1970 issue of Green Lantern, which added Green Arrow as a title character. The series, written by Denny O'Neil and penciled by Neal Adams (with inking by Adams himself or Dick Giordano), focused on "relevance" as Green Lantern was exposed to poverty and experienced self-doubt.

The death of Spider-Man's girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, at the hands of the Green Goblin in Amazing Spider-Man #121-122 (June-July 1973) is considered by comics scholar Arnold T. Blumberg to be the definitive Bronze Age event, as it exemplifies the period's trend towards darker territory and willingness to subvert conventions such as the assumed survival of long-established, "untouchable" characters. However, there had been a gradual darkening of the tone of superhero comics for several years prior to "The Night Gwen Stacy Died", including the death of her father in Amazing Spider-Man #90 (November 1970) and the beginning of the Dennis O'Neil/Neal Adams tenure on Batman (Detective Comics #395, January 1970).

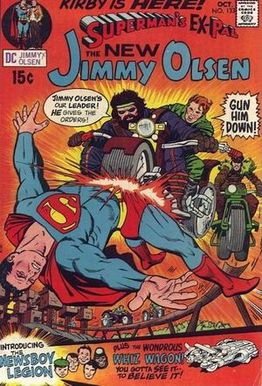

Later in 1970, Jack Kirby left Marvel Comics, ending arguably the most important creative partnership of the Silver Age (with Stan Lee). Kirby turned to DC, where he created The Fourth World series of titles starting with Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #133 (December 1970).

The Passing Of THe Torch

In 1970, Mort Weisinger, the long term editor of the various Superman titles, retired to be replaced by Julius Schwartz. Schwartz set about toning down some of the more fanciful aspects of the Weisinger era, removing most Kryptonite from continuity and scaling back Superman's nigh-infinite—by then—powers, which was done by veteran Superman artist Curt Swan together with ground-breaking author Denny O'Neil.

The beginning of the Bronze Age coincided with the end of the careers of many of the veteran writers and artists of the time, or their promotion to management positions and retirement from regular writing or drawing, and their replacement with a younger generation of editors and creators, many of whom knew each other from their experiences in comic book fan conventions and publications. At the same time, publishers began the era by scaling back on their super-hero publications, cancelling many of the weaker-selling titles, and experimenting with other genres, such as horror and sword-and-sorcery.

The beginning of the Bronze Age coincided with the end of the careers of many of the veteran writers and artists of the time, or their promotion to management positions and retirement from regular writing or drawing, and their replacement with a younger generation of editors and creators, many of whom knew each other from their experiences in comic book fan conventions and publications. At the same time, publishers began the era by scaling back on their super-hero publications, cancelling many of the weaker-selling titles, and experimenting with other genres, such as horror and sword-and-sorcery.

Diversifying, Scaling Back

In 1970, Marvel published the first comic book issue of pulp character Conan The Barbarian. Conan's success as a comic hero resulted in adaptations of other characters of Robert E. Howard: Kull, Red Sonja, Solomon Kane. DC Comics responded with Warlord, Beowulf, and Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. They also took over the licensing of Edgar Rice Burroughs's Tarzan from long-time publisher Gold Key, and began doing adaptations of other Burroughs characters such as John Carter: Warlord of Mars, the Pellucidar series and the Amtor series. Marvel also adapted to comic book form, with less success, Edwin Lester Arnold's Gullivar Jones Of Mars and later Lin Carter's Thongor of Lemuria.

At the beginning of the 1970s, publishers moved away from the super-hero stories that enjoyed mass-market popularity in the mid-1960s; DC cancelled most of its super-hero titles other than those starring Superman and Batman, while Marvel cancelled weaker-selling titles such as Dr. Strange, Sub-Mariner and the X-Men. In their place they experimented with a wide variety of other genres, including the Westerns, horror and monster stories, and adaptations of pulp adventures mentioned above. These trends peaked in the early 1970s, and the medium reverted by the mid-1970s to selling predominantly super-hero titles.

At the beginning of the 1970s, publishers moved away from the super-hero stories that enjoyed mass-market popularity in the mid-1960s; DC cancelled most of its super-hero titles other than those starring Superman and Batman, while Marvel cancelled weaker-selling titles such as Dr. Strange, Sub-Mariner and the X-Men. In their place they experimented with a wide variety of other genres, including the Westerns, horror and monster stories, and adaptations of pulp adventures mentioned above. These trends peaked in the early 1970s, and the medium reverted by the mid-1970s to selling predominantly super-hero titles.

Relaxing The Comics Code Authority

In 1971, Marvel Comics Editor-in-Chief Stan Lee was approached by the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to do a comic book story about drug abuse. Lee agreed and wrote a three-part Spider-Man story, "Green Goblin Reborn!," which portrayed drug use as dangerous and unglamorous. At that time, any portrayal of drug use in comic books was banned outright by the Comics Code Authority, regardless of the context. The CCA refused to approve the story, but Lee published it regardless.

The positive reception that the story received led to the CCA revising the Comics Code later that year to allow the portrayal of drug addiction as long as it was depicted in a negative light. Soon after, DC Comics had their own drug abuse storyline in Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85-86. Written by Denny O'Neil with art by Neal Adams, the storyline was entitled "Snowbirds Don't Fly," and it revealed that the Green Arrow's sidekick Speedy had become addicted to heroin.

The 1971 revision to the Comics Code has also been seen as relaxing the rules on the use of vampires, ghouls and werewolves in comic books, allowing the growth of a number of supernatural and horror-oriented titles, such as Swamp Thing, Ghost Rider and The Tomb of Dracula, among numerous others. However, the tone of horror comic stories had already seen substantial changes between the relatively tame offerings of the early 1960s (e.g. Unusual Tales) and the more violent products available in the late 1960s (e.g. The Witching Hour, revised formats in House of Secrets, House of Mystery, The Unexpected).

The positive reception that the story received led to the CCA revising the Comics Code later that year to allow the portrayal of drug addiction as long as it was depicted in a negative light. Soon after, DC Comics had their own drug abuse storyline in Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85-86. Written by Denny O'Neil with art by Neal Adams, the storyline was entitled "Snowbirds Don't Fly," and it revealed that the Green Arrow's sidekick Speedy had become addicted to heroin.

The 1971 revision to the Comics Code has also been seen as relaxing the rules on the use of vampires, ghouls and werewolves in comic books, allowing the growth of a number of supernatural and horror-oriented titles, such as Swamp Thing, Ghost Rider and The Tomb of Dracula, among numerous others. However, the tone of horror comic stories had already seen substantial changes between the relatively tame offerings of the early 1960s (e.g. Unusual Tales) and the more violent products available in the late 1960s (e.g. The Witching Hour, revised formats in House of Secrets, House of Mystery, The Unexpected).

Alternate Markets

This era also encompassed major changes in the distribution of and audience for comic books. Over time, the medium shifted from cheap mass market products sold at newsstands to a more expensive product sold at specialty comic book shops and aimed at a smaller, core audience of fans. The shift in distribution allowed many small-print publishers to enter the market, changing the medium from one dominated by a few large publishers to a more diverse and eclectic range of books.

DC Implosion

In the mid-'70s, DC launched numerous new titles such as Jack Kirby's New Gods and Steve Ditko's Shade The Changing Man. The company referred to this as the DC Explosion.

Since the early 1970s, DC had seen its dominance of the market overtaken by Marvel Comics, partly because Marvel had significantly increased the number of titles it published (both original material and reprint books). In large part, the DC Explosion was a plan to overtake Marvel at its own game.

DC instead experienced ongoing poor sales in the winter of 1977. This has been attributed in part to the North American blizzards in 1977 and 1978, which both disrupted distribution and curtailed consumer purchases. Furthermore, the effects of ongoing economic inflation, recession, and increased paper and printing costs cut into the profitability of the entire comic book industry, coupled with steadily decreasing numbers of readers. In response, company executives ordered that titles with marginal sales and several new series still in development be cancelled.

During these meetings, it was decided that DC's long-running flagship title Detective Comics was to be terminated with #480, until the decision was overturned following strenuous arguments on behalf of saving the title within the DC office, and Detective was instead merged with the better-selling Batman Family.

On June 22, 1978 DC Comics announced staff layoffs, and the cancellation of approximately 40% of its line. Marvel eventually gained 50% of the market and Stan Lee handed control of the comic division to Jim Shooter while he worked with their growing animation spin-offs.

Since the early 1970s, DC had seen its dominance of the market overtaken by Marvel Comics, partly because Marvel had significantly increased the number of titles it published (both original material and reprint books). In large part, the DC Explosion was a plan to overtake Marvel at its own game.

DC instead experienced ongoing poor sales in the winter of 1977. This has been attributed in part to the North American blizzards in 1977 and 1978, which both disrupted distribution and curtailed consumer purchases. Furthermore, the effects of ongoing economic inflation, recession, and increased paper and printing costs cut into the profitability of the entire comic book industry, coupled with steadily decreasing numbers of readers. In response, company executives ordered that titles with marginal sales and several new series still in development be cancelled.

During these meetings, it was decided that DC's long-running flagship title Detective Comics was to be terminated with #480, until the decision was overturned following strenuous arguments on behalf of saving the title within the DC office, and Detective was instead merged with the better-selling Batman Family.

On June 22, 1978 DC Comics announced staff layoffs, and the cancellation of approximately 40% of its line. Marvel eventually gained 50% of the market and Stan Lee handed control of the comic division to Jim Shooter while he worked with their growing animation spin-offs.

Ending & Neo-Silver Movement

The end of the Bronze Age is debatable. One commonly used ending point for the Bronze Age is the 1985-1986 time frame. As with the Silver Age, the end of the Bronze Age relates to a number of trends and events that happened at around the same time. At this point, DC Comics completed its event, Crisis On Infinite Earths (April 1985-March 1986), which marked the revitalization of the company's product line to become a serious market challenger to Marvel again.

The 1985-1986 time frame also includes the company's release of the highly acclaimed works, Watchmen (by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons) and The Dark Knight Returns (by Frank Miller), which redefined the superhero genre and inspired years and years of "grim and gritty" comic books.

At Marvel Comics, the commonly used milestone marking the end of the Bronze Age is Secret Wars, although this could be extended to 1986, which saw the cancellation of Defenders and Power Man & Iron Fist, as well as the launch of the New Universe and X-Factor (an extension of the X-Men franchise).

According to historian Peter Sanderson, the "neo-silver movement" that began in 1986 with Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? by Alan Moore and Curt Swan, was a backlash against the Bronze Age with a return to Silver Age principles. In Sanderson's opinion, each comics generation rebels against the previous, and the movement was a response to Crisis On Infinite Earths, which itself was an attack on the Silver Age. Neo-silver comics creators made comics that recognized and assimilated the more sophisticated aspects of the Silver Age.

The 1985-1986 time frame also includes the company's release of the highly acclaimed works, Watchmen (by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons) and The Dark Knight Returns (by Frank Miller), which redefined the superhero genre and inspired years and years of "grim and gritty" comic books.

At Marvel Comics, the commonly used milestone marking the end of the Bronze Age is Secret Wars, although this could be extended to 1986, which saw the cancellation of Defenders and Power Man & Iron Fist, as well as the launch of the New Universe and X-Factor (an extension of the X-Men franchise).

According to historian Peter Sanderson, the "neo-silver movement" that began in 1986 with Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? by Alan Moore and Curt Swan, was a backlash against the Bronze Age with a return to Silver Age principles. In Sanderson's opinion, each comics generation rebels against the previous, and the movement was a response to Crisis On Infinite Earths, which itself was an attack on the Silver Age. Neo-silver comics creators made comics that recognized and assimilated the more sophisticated aspects of the Silver Age.